REVIEW (FILM): DEATH NOTE

/Disclaimer: I have nothing in particular against adaptations. There is some conflict of interest when I talk about Death Note, however. I am a fanboy. I avidly followed weekly fan-made scanlations as the original manga appeared in Weekly Shonen Jump. I shared it with any classmate who would listen and would re-read previous chapters during breaks. For god’s sake, I have a Death Note in my desk drawer (hidden in a spring-loaded self-destruction compartment, of course — do not fuck with me). And what’s more, I think Death Note was always ripe for adaptation. What makes its concept so compelling is not rooted in its Japanese context (unlike in the cases of, say, Akira, or Ghost In the Shell), but in its mechanics, exposition, and tone.

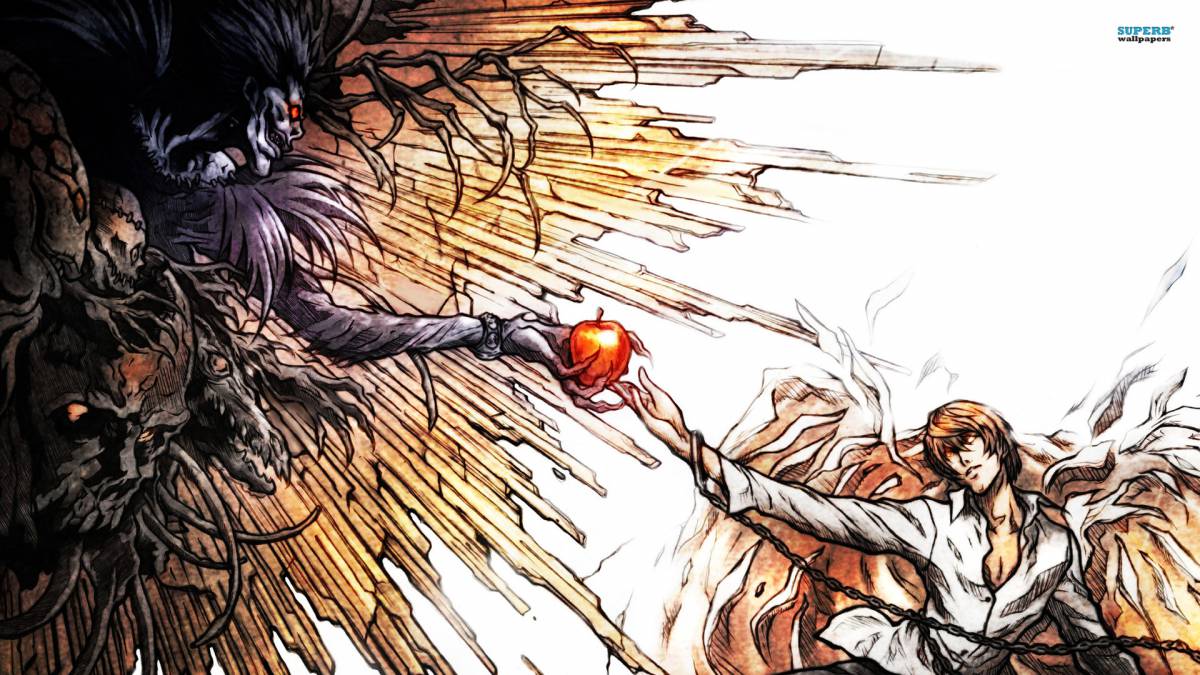

Plus, the film was shot in my city. I knew people who worked on it. Willem Dafoe sold the trailer for me — between the psychopath and autistic supergenius headliners, the chuckling death god Ryuk was always the closest thing to a relatable character, as detached outsider, out of the whole cast, and Dafoe’s rasping, meandering delivery nails this crossroads between horror and chillness. I was ready to love this movie.

Unfortunately, for all its courageous adjustments to the medium, Death Note is riddled with tone-deaf faceplants.

The story common to all versions of Death Note is this: When a demon drops a notebook with the power to kill anyone whose name is written in it into the world of the living, teenage genius Light takes it upon himself to become a self-styled god of justice and cleanse the world of criminals and wrongdoers. However, when his untraceable killings reach an epidemic scale that attracts the admiration of people around the world who worship him as “Kira” (Japanese approximation of “Killer”), he also draws the attention of elusive international super-detective “L”. An intellectual cat-and-mouse game of epic proportions ensues.

The adaptation to a Western cultural setting comes with obvious changes; Seattle instead of Tokyo; an evil demon instead of a casually funny one; a high-IQ outcast instead of a socially popular career-student. Even as a fan of the manga and anime, these changes don’t bother me at all. They are part and parcel of the need to localize and adapt to feature-length film. Japanese culture has an easy-handed familiarity with the notion of spirits surrounding us. American culture does not. Academic achievement is a marker of social status in the East, and of unwanted weirdness in the West. However, other changes are more glaring. Why is the main character’s name “Light” ? That is not an English name (The script’s desperate effort to justify his accent-mocking “Kira” moniker is laughable). Why is the mysterious super-detective “L” introduced in person before we’ve even had a chance to wonder who or what this entity might be? Why the ironic choice of music at the moment of a crucial character death (trust me — you’ll know) ? I don’t even gripe as a fan; I gripe as a watcher of movies, bewildered at the things the writers chose not to change, when it seemed everything else was up for grabs.

Character development is a core strength of the original series. Light & L’s similar-yet-different takes on cold, calculating brilliance form the basis of a relationship that could be called true love, while they unknowingly (and not-so-unknowingly) work against each other. L invites Light to join to the investigation even as he suspects Light to be a supernatural mass-murderer — because it will make it easier to investigate him. In the books, Light is unfazed by this development, for now he, too, can gain more intel on L’s maneuvers against him. And so the moves and counter-moves and deceptions and intrigues accumulate upon each other throughout the story, all the while, L openly telling Light the current likelihood of his guilt to the percentile, and Light gaining more and more knowledge of the complex legalese which restricts the Death Note's power. The social and intellectual tension between these characters, and others, absolutely crystallizes Death Note as a classic work of literature.

I only look back to the manga here, to highlight the flaws of the film. The script ties itself in knots trying to make Light into a relatable character. At Ryuk’s blustering first appearance he shrieks “What the fuck!!” cowering beneath a teacher’s desk. He says stupid things to bullies to impress a girl he likes, getting himself punched out and thrown in detention. Life with his cop single-dad is okay, but not great. But Light was never supposed to be relatably mediocre; he was supposed to be a kind of best-and-worst possible candidate to own a magical murder book, a paragon ambassador to the realm of the death gods, just a little too eager to kill people by the thousands to deserve that right. His behaviour is simply too grotesque to match up with the “cute teen” look the movie seems to reach for, and the final act even seems to apologize for, and forgive, his disgusting actions. Maybe the script is to blame, but Nat Wolff plays more the tortured lovechild of a boyband dropout and a school shooter, than a cool & collected nu-god of justice.

L’s portrayal is more endearing. He gobbles candy in messy fistfuls — the insulin spikes are needed for cognitive breakthroughs, you see — and tracks his abhorrent sleep patterns by the hour. He skulks, and perches, and mutters, and otherwise embodies all the habits of the ultimate eccentric. I commend Stanfield’s interpretation of the character for its honesty and clarity. Unfortunately, the script fails to provide the brilliant tactical overtures which define the other half of L’s eccentricity: the whole genius thing. He makes one or two cool deductions and gambits to pull the rug out from under the man he suspects. But where Death Note really fails is in the lack of almost-hilarious “I knew you knew that I knew what you thought I was going to do, but…” moments which drive tension in the comics.

The core problem of the Netflix Death Note, I think, is its imprisonment in adaptation land. It really could have flown, if the writers felt they had the freedom to simply write a story in the Death Note universe, with all the charms and trappings of its complex internal logic, while not being yoked to the particulars of the source material. A small, city-scale conflict between an angry teenager and Seattle’s best detective would have been a fitting context for the movie we got. Instead, we have a movie that tries & fails to directly reproduce literary genius. It underwrites brilliance. There’s no shame in being dumber than your characters, when your characters are Einstein-tier uber-geniuses. But when the thrill of the story rides on their apparent ingenuity, then you have a problem. Death Note is not just a story of corrosive power; it’s also a story of social entanglement, where the ones you love may be the ones you need to destroy, and all the muddled morals in between. And it plays out on the landscape of the world’s two most brilliant minds, carefully mapped out, so that the reader, too, feels as intelligent as them. In the end, Death Note turns out to be a decent film with some tone-deaf flubs, but a terrible adaptation of a brilliant story.

3/10