GAMING AIN'T FILM

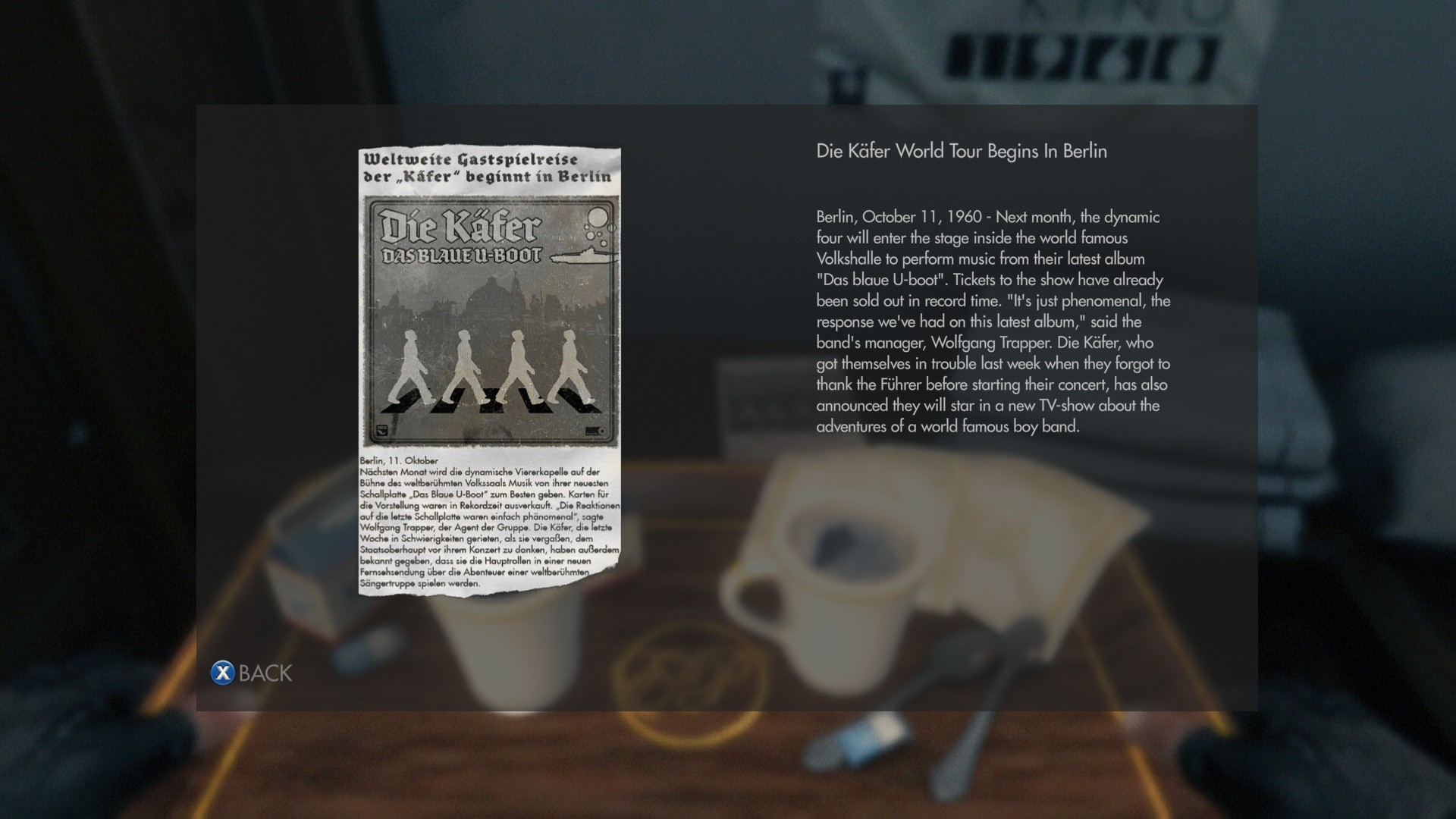

/As I was playing through 2014’s Wolfenstein: The New Order a little while ago it occurred to me that I was playing a great movie. After a few fervent early missions killing robotic mega-Nazis, you enter a peaceful homebase area and interact with a small cast of friendly characters. As I spoke to each of the rough-and-tumble renegades, scoured their candlelit quarters for juicy backstory details, and trawled through countless newspaper articles describing the establishment of the totalitarian Nazi superpower across the globe through the 40s and 50s, I realized I was part of a story that desperately wanted to be told in full. Much like a movie, it felt as if Wolfenstein wanted me to see each minute detail of its story piece by piece until everything came together in my mind. The key thing here is that the game wanted me to SEE these details -- and not PLAY them…

Don’t get me wrong. I really enjoyed New Order overall, and I’d recommend it. But as a game it’s just mediocre. Strip away all these rich story details, tense dialogue exchanges (which you don’t control; you just sort of watch your character talk), and lovable characters, and you’ve got a fairly inarticulate dual-wielding run-and-gun corridor FPS game. If the writing had been weaker, I don’t think I would have been motivated to grind through some of the more tedious “DO THIS THING HERE!” challenges that the game inelegantly chucks you into. But it carries so well as a movie you want to know the ending to, that the anemic gameplay passes as fun a lot of the time. And this identifies a blurring line between games and film as the former continues to balloon as an industry -- what other entertainment medium has grown so large, so quickly?

In the wake of the financial success of consoles in the 90s, the largest budgets for videogame production are rising to compete with Hollywood films, with the star talent, CGI, and marketing campaigns to match. A co-worker of mine told me he’s interested in gaming: he moonlights as a foley guy for TV and commercials, and he suspects that videogames are where the real money is nowadays -- even for an industry as film-niche as sound production.

However I think this is a mistake. I think the real similarity between movies and gaming pretty much ends at budgetary magnitude. To treat gaming as just… home video in a different type of VCR sells it short of its potential, and leads to exploitative licensing cash-ins like the new Star Wars videogame. I do appreciate that some games work well as kind of surrogate films (looking to aforementioned Wolfenstein and Metal Gear Solid) but these linear narratives really feel like they sprawl too wide and deep to be contained in the silver screen; they take advantage of the affordances of gaming to tell a bigger story. And in the rare cases where the depth of gameplay matches the depth of story, nothing’s more fun. These days, many AAA titles aim to awkwardly recreate the cinematic experience through a controller and the result is usually a deadened game and a dull movie. I played through Hitman: Absolution and Deus Ex: Human Revolution when I built my PC last year, and both games seem to sacrifice so much of their well-loved gamey-ness for a dull, mass-appeal movie-ness. No player sits down and hopes not to push any buttons in a 10 minute interval. The difference in appeal between literary depth, and interactive depth, should be respected.

I mean, even in name they indicate something radically different. The whole activity of film isn’t called “movie-ing.” It’s too passive. As a medium, it’s called film or cinema - a simple noun. As a whole activity, the other medium is referred to as gaming - a present-tense verb; something that is being done. There’s plenty of room for flexing the semantics of this distinction but regardless it can be agreed upon that gaming needs to take a different industrial arc than film does, so those massive pools of resources can fuel innovation and interactivity, and not just mass-appeal spectacles.