MOVIE REVIEW: A DREDD-FUL DISAPPOINTMENT

/I'll be honest, I never read the 2000AD Judge Dredd comic, and I never saw the 1995 Stallone movie. My knowledge of Judge Dredd was limited to a brief magazine review of the 2003 video-game adaptation, and entailed Dredd's access to some interesting types of bullets for his gun. I'm not sure what compelled me to see 2012's Dredd, other than some vague recommendations by a friend or two and a general desire last night to get back into watching action movies. For these reasons I was able to watch Dredd as "just a movie," with no expectations.

Turned out no expectations was still too many.

Dredd is a day in the life of Joseph Dredd, a high-powered police Judge in the post-nuclear dystopia of Mega-City One, USA. Walled off from the irradiated wasteland that is the rest of the continent, and possibly the world, Mega-City One is a single, continuous, sprawling urban landscape (punctuated by 200+ storey, brand-named Megastructures) that spans most of the Northeast region of the USA. Since life in this society has been mostly insulated from the nuclear devastation outside, corporate monopoly, economic inequality, and state control have run rampant. Surveillance drones casually oversee 16-highway intersections, and offenses as basic as begging are punishable by several weeks in solitary confinement. Understandably, this claustrophobic situation has led to a lot of poverty, gang crime, and violent resistance against the systems of control. Enter the Judges: a new breed super-cop with advanced weaponry and apparently unlimited use-of-force rights when it comes to fighting crime. Dredd himself is a paragon among them, his reputation for dispensing merciless justice unrivaled. There is just... so much to work with here!

EXTREMELY BRIEF PLOT SYNOPSIS (SPOILERS AHEAD)

After witnessing how badass Dredd (Keith Urban) is, we see him assigned a psychic mutant rookie recruit by the name of Cassandra Anderson (Olivia Thirlby). Dredd goes full hard-ass on her but she doesn't seem phased. Together they check out a few dead bodies at the ghettoized Peach Trees Mega-Structure - the victims skinned and intoxicated before being thrown to their deaths - and Anderson's recruit assessment turns into a lethal grind up 200 stories of brutal gang violence. Once the "ex-hooker"-turned-druglord Ma-Ma (played by a much, much mellower Cersei Lannister) catches wind of a Judge on her turf, she locks down the Mega-Structure and engages the Judges with thugs, gatling guns, and traitorous, bounty-hunting Judges of her own. Dredd has his doubts about Anderson's ability to cope with the job, but through the use of her psychic abilities and fighting prowess, she proves so useful in the final takedown of the gang that Dredd forgives her many transgressions of Judge policy. Yet when they finally throw Ma-Ma from the top floor of the building and meet reinforcements, Anderson gives Dredd her badge and walks off, while Dredd tells the Chief Judge she was a Pass. Roll credits.

GRIPE 1: CHARACTERS.

DREDD: Judge Dredd is basically Robocop with Duke Nukem neuro-software. Ruthless, efficient, perpetually grimacing and ever-helmeted. I love it. Trouble is, the movie never, not once, questions his generous use of violence. Why is Dredd so committed to the profession? Was he orphaned and brought into training, like Anderson? Is he overcompensating for a guilty criminal past? And why doesn't Dredd work with a partner, like other Judges seem to? This would have been such a perfect place for the old stereotype of the dead partner - maybe Dredd starts to slip up in attempts to stop another partner from dying (even after warning Anderson that 1 in 5 recruits die during assessment). At the very beginning of the movie, Anderson psychically probes Dredd, and sees... something else... behind his severe interpretation of the law -- yet this is never followed up on !! I was positive the movie would go on to develop Anderson's growing understanding of the monster inside the man she'd been assigned to - about his history and motivations - but Dredd's character arc throughout the movie is completely static. He doesn't learn, he doesn't change; nothing even seems to surprise him. Not only do we have no way of relating to Dredd through backstory or exposition; we have no reason to really admire him, because he spends the whole movie just enforcing the rules he's been taught.

ANDERSON: Dredd works so hard to establish Anderson is the atypical strong female that she ends up having very little character to hold onto - though I must admit I was relieved there was a reason she was the only Judge not wearing a helmet (it interferes with her mind-reading). Early in the movie, Dredd pushes her to execute a... drug-user (??) in a bust, and her guilt is magnified when the dead man's wife later helps them evade the gangsters. There seems to be a dangerous sympathy that accompanies her telepathy, but this is quickly abandoned. Anderson hesitates, but never doesn't kill people. After her first killing, Anderson expresses no further agency other than at the end, where she walks off the force. She doesn't explore what it means to be a Judge, or how she can really make the world a better place; she just does the job perfectly, and then rejects it. This is a wasted opportunity for what should've been an interesting character arc. Lastly, through the first two acts of the movie, we get several references to Anderson's mutant status - in the Judge Dredd universe, mutants are a reviled minority of deformed freaks, with Anderson being the attractive exception - yet we don't see one single mutant throughout the movie, not even among the drug- and crime-dependent poor who comprise the enemy ranks. Why make reference to mutants if they don't even factor in? It's just half-assedly being "true" to the source material.

MA-MA: Cersei Lannister is the least enjoyable part of the movie. While in Game of Thrones this is because of her well-written and acted yet impossible-to-like character, in Dredd, her character is so ... not... character-y that there is just nothing to work with. In most of her scenes she is just sort of overseeing violence carried out by her lackeys - but we're never given a reason to fear or loathe her. She is an "ex-hooker" and "known for extreme violence" - but in her vague background montage, we never actually SEE her do anything evil! In a way, she cleaned up the Peach Trees mega-structure when she eliminated the rival gangs (all lead by characters whose mugshots suggest they would have made way more interesting villains) and conquered the totally unpoliced building. It's specifically said that Judges rarely come out to Peach Trees. Ma-Ma filled in the void and brought order to the place. Even her appearance is totally halfhearted as she croaks and mutters orders at her ethnically ambiguous drones - she wears absolutely no signifiers of wealth or power. How do you become a drug Queen in postnuclear America without getting some fucking bling, some cool guns, SOMETHING!? Nothing about the direction, photography, script, or performance suggest that Ma-Ma is remotely special in the criminal landscape of Mega-City One. There's no personal connection between her and Dredd, so there's no tension building up to the confrontation with her. It's just a generic conflict between crime and the law and it has no impact.

Imagine if this had been a grudge match - if Ma-Ma was an infamous Judge-killer, had their uniformed and helmeted corpses strung up and crucified throughout her turf, and that was why nobody answered calls out here anymore. What if Ma-Ma was a significant, and justified, political opponent against the rampant, institutionalized violence that characterizes Mega-City One's psychopath police force? Or, let's get Swiss-cheesy here: what if Ma-Ma had been the one who killed Dredd's ex-partner? Wore his bloodied helmet into battle against him, psychologically tortured him with guilt over his failures? Dredd tells the story of a cop versus a criminal - with just a few scripting changes, it could've been the story of The Cop against The Criminal: politically charged, just as violent, and way, way more intense.

GRIPE 2: ACTION AND PACING.

Towards the end of the first act, Ma-Ma cajoles her computer nerd into hacking building security to lock in the Judges. This is a big moment; innocent people eating their snacks and watching TV look around in confusion as the ceiling closes out sunlight and blast doors drop down to block all entrances - then the power goes out and the whole complex is awash in pure-red emergency lighting. For a fleeting moment, I was so excited by the artistic potential in this - for a movie playfully deconstructing rampant police brutality to run all its action sequences in a relentless palette of black and red - Heck, this even would have set up a few frames to boldly recreate two-tone frames from the original comic, a la Sin City - and yet within seconds, an emergency generator kicks in and natural lighting is instantly restored. This is one of many instances of Dredd ignoring its own potential for intense action.

Dredd weighs itself in as a sci-fi action movie, and while the sci-fi aspects it draws on from its source material are cool as fuck, the action bits are terribly executed. This might be excusable considering the apparently low budget for this film, but I think it just comes down to laziness. There is something that seems not only boring, but bored, about the choreography. For instance, the opening scene features Dredd chasing down a, I guess, hippie van (??) on a busy highway. Trouble is he does only and literally that. The camera cuts back and forth between a shitty van and a "tactical" motorcycle driving in a straight line. They change lanes a few times, but their driving is, overall, nice and safe. Then the van hits a pedestrian, Dredd blows out their tires with motorbike machine-guns, the van flips, and the enemies are mostly dead. Dredd hunts down the remaining survivor to an empty mall, disregards the hostage he's taken, and fires an incendiary round that slowly immolates its way from his mouth through the back of his skull. It's badass that Dredd is so decisive and imperturbable - but at the same time he so rarely does anything interesting. He points and he shoots; it's like he's playing a video-game. Mass murder is routine for Judge Dredd - he even walks Anderson through tactical protocol - but it comes off as totally unimpressive rather than ruthlessly callous, and it actually rings hollow when he literally runs out of bullets when cornered by his rival, Judge Lex.

The script just doesn't seem to have any grasp on the psychology of tension. In the battle with Lex it's actually difficult to tell Dredd and Lex apart - they have the same helmet, uniform, skintone, and jawline. We don't know who to root for, or who's getting the upper hand until the characters are at a distance from each other. Dredd runs out of ammo and hides behind a pillar, while Lex approaches and delivers a single line that should have been the core conflict of the entire movie; to paraphrase, "this city's a meatgrinder, and us Judges just crank the handle." Lex then fires an armour-piercing round through cement that seriously injures Dredd. And what happens next, right at the critical moment where Dredd must finally prove his worth, going above and beyond protocol, human limitations, and outrageous odds? Anderson walks in from behind and shoots Lex dead. Dredd effortlessly heals his injury and the brush with death is forgotten. Dredd's one moment of weakness is executed in a humourless and anticlimactic way.

Earlier, there's a showdown with Ma-Ma when she intercepts the Judges as they ascend the Mega-Structure. For some reason, she has three mounted gatling guns, which somehow shoot lasers and yet still chug out spent shells, and uses them to decimate the entirety of the building floor, waggling them around in the general direction of Judge Dredd. She and her gang just stand there, combing back and forth with stationary guns through dozens of feet of Rebar and concrete, while Dredd casually stalks from cover to cover. There's just no tension here at all. After the onslaught, Dredd walks out and faces her from the opposite balcony as she literally stands at her gatling gun, peaceably accepting his confrontation immediately after fully committing to demolishing her home in order to destroy him.

Every sequence in between these highlights is like a bad FPS stage. Pop outfrom a corridor, kill a guy. Continue forward. Hide behind a corner. Kill a few other guys. Snarky comment. Chuck a grenade, then execute the incapacitated. Rinse and repeat. There is no feeling of mounting pressure to succeed. New problems just kind of come up and are quickly dispensed with.

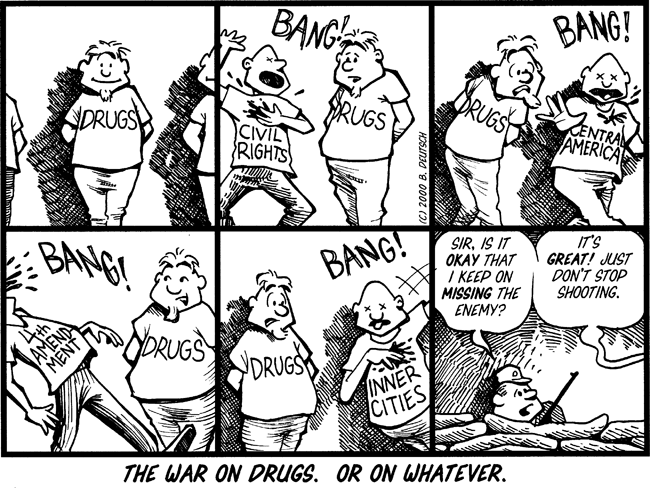

GRIP 3: THE MESSAGE.

Ok. So I'm being hard on Dredd. I know it has lots of fun moments. I know it's just a dumb machismo action flick. But I loved the concept of this movie. I got the impression that the first 15-20 minutes was more dependent on the original comic than the rest, because it so clearly set itself up to be a massive work of satire. The relatable, sensitive, outcast psychic; the blunt-force, dogmatically law-abiding, ultraviolent Dredd himself; the constant foreshadowing that the chaos and violence in the city is the result, not cause, of inequality and state-sanctioned brutality. Without being too cheesy, in order to connect with the audience, the ultimate revelation needed to be that Judge Dredd is completely in the wrong. He's not a hero; he's just a peon, a slave to a system with no regard for the lives of impoverished minorities. Dredd is only in his element among the bloodbath of the action sequences; he depends on violence and crime in order to even exist. This dependence - the dependence of martial law on a perceived enemy - is never explored. The whole mystique of the masked vigilante is the fleshy weakling within -- who is this psychologically broken man? As it is now, the message more or less seems to be "The war on drugs has been a success and some people just aren't up for the job."

In a setting like Mega-City One, this is a complete waste of an opportunity for a movie that could have been just as fun and violent, but also hilarious, satirical, and critically well-informed.